The Wind

An interview with David Ruben Piqtoukun

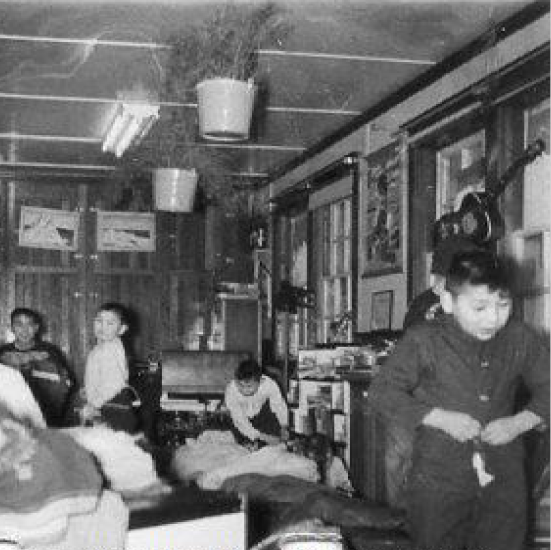

Q. Tell us about your childhood.

When I was born I was given the name of an old man who befriended my parents. Traditionally, when someone passes away, a newborn would be given their name. I was known as Piqtoukun which means 'the wind'

We were 17 siblings in the family. My earliest memory is the freezing cold. (In Inuvialuktun we say 'alappa'.) Especially my fingers when I forgot to wear mitts.

Photo: NWT Archives

When I was five, my parents were out hunting and strange men came and collected us kids. They scooped us up like a shovel and threw us in an plane. I remember the drone of the engines and the cold. My sister and cousins, we didn't know where we were going.

When we arrived, they shaved our heads to make sure we didn't have lice. ('Gumuq' in Inuvialuktun). We were under strict supervision. We were not allowed to speak our language. They said: 'Obey our rules.'

Photo: NWT Archives

Q. Were you frightened?

I was terrified. With my anger, I damaged many things and took a lot of physical abuse. In the classroom, the teachers pulled my ears until they bled. They whacked my head with wooden rulers.

I was a poor learner so I spent my time sketching Arctic animals from Paulatuk to maintain my sense of sanity and well-being.

Photo: NWT Archives

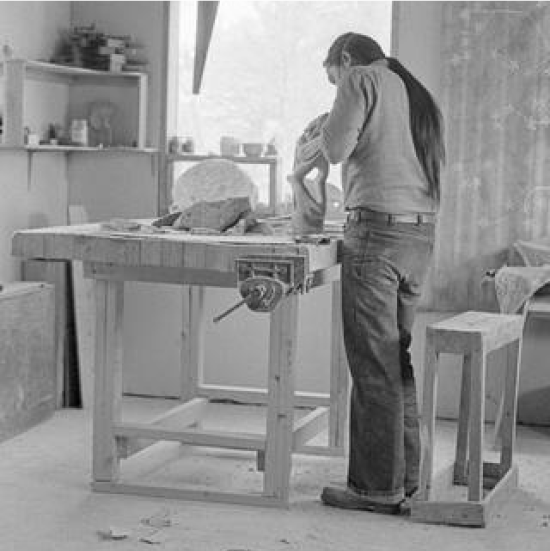

Q. How did you become an artist?

In 1972 my brother, Abraham, came back from Alaska where he had taken instruction on stone carving at the University in Fairbanks. After a few months of his instruction, he left for studies. I was on my own.

I went to local libraries and picked up books on Eskimos and Arctic animals. This allowed me to make my first stone carving attempts. It was a way of exploring who I was.

Photo: NWT Archives

Q. How did you learn about legends?

In Paulatuk in the 1950s, the only forms of entertainment were storytelling and home-grown music. The stories excited my imagination.

But it wasn't until the 1970s, when I began carving, that I understood how important these stories were. Without a story, a block of stone wouldn't speak to me. So I collected stories from my village and I made stone carvings.

Photo: Courtesy of David Ruben

Q. How long did it take to learn to carve?

I find beauty in stone: the colour, the texture, the shape. But it took four years to make a carving that looked the way I wanted. I wanted to learn so badly, I kept going, I never gave up.

It took another ten years to refine a piece of rock, to make it look beautiful. Once I got the first beautiful carvings out, that established my efforts.

Photo: Courtesy of David Ruben

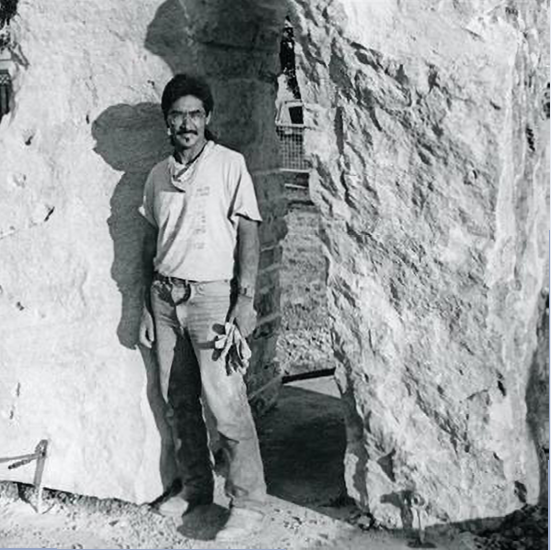

Q. Do you use your experiences on the land?

Yes. As a young fellow I had a boat in Darnley Bay. It was August and the ocean was like glass. I had motor trouble so I was making a lot of noise with the tools. I attracted a massive ugiuk, a giant male seal. It popped up at the bow of the boat and looked at me.

It scared me. I tried to grab my gun but I'm glad I didn't. I sat back and watched it fall back in the ocean.

Photo: Inuit Gallery of Vancouver

Q. Animals feature in your work...

When I was 17 years old, I was trapping foxes to help out my parents. In March, I caught a fox that surprised me. I broke its neck, and then I gathered up my traps and started to head back home. And I saw the fox running away from me. It ran and ran.

It was like a anutkok, a spirit creature. That was the end of my trapping career. I haven't killed an animal since.

Q. What message are you sending to youth?

I collect stories and transform them into images so that they last. I hope my experience will be useful for young carvers, to encourage them to carry on the tradition.

My message is: Don't be afraid to collect stories. Poke older people. Say to them: "Tell me your story". One day, someone will want to transform that story into a carving.

Photo: Charlie Ross